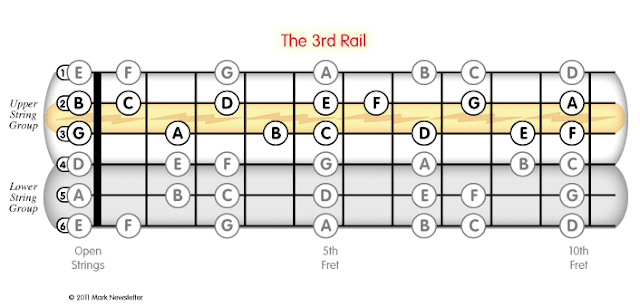

So far we've examined the 7th chord forms which radiate around the 3rd Rail – that problematic nexus of the 2nd and 3rd strings. By treating it as a fulcrum or the center of gravity of the fret board, it becomes a useful organizing element. No longer a problem, but a solution.

Here's the interval structure of the four types of diatonic 7th chords in the major keys, based on the major and minor 3rds which occur between each chord degree;

Notice that the major 7ths and minor 7ths have opposite interval structures. The same opposing symmetry is true of the V and VII chords. Because these symmetries are integral to the chords' structure, it's logical that they play out on the fret board as geometrically symmetrical patterns.

The center interval in each of these 7th chords spans the 3rd Rail. Only the minor 7th chords have a major 7th in their centers. It takes a change in perspective to think of chords from the center outward, rather than from the bottom up, but it will give you a much more sophisticated understanding of harmony and a greater command of the fret board.

The three minor 7th chords are rooted on the 2nd, 3rd and 6th scale degrees of a major key. The major 3rds at the center of these chords are rooted on the 4th, 5th and 1st scale degrees, respectively.

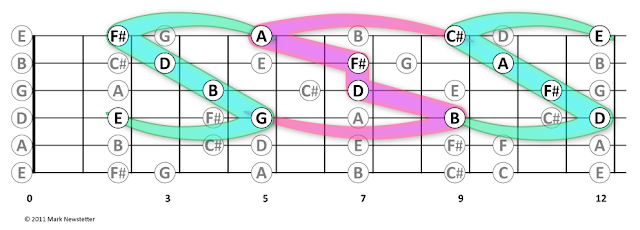

The I - IV - V center intervals on the 3rd Rail are essential landmarks on the fret board. We've already examined these positions in this post. The next diagram shows all the major 3rds spanning the 3rd Rail up to the 17th fret (If your guitar has 24 frets then you also get one there);

The minor 7th chords rooted on the 4th string all pass through the above positions;

If we extend these 7th chord forms a 3rd above and below, we then have a set of 11th chords;

We have previously treated these low note extensions as integral parts of the 7th chords, but now we'll look at them in their own light. We'll start with the chord which radiates from the central axis position; the 5th fret in the key of C where the tonic major 3rd is positioned;

In this position – starting from the center and moving outward – we first find the C major 3rd (C-E), the A minor 7th chord (A-C-E-G), then the F major 11th (more precisely F major 7 #11), consisting of six notes (F-A-C-E-G-B). So this form is, starting from its lowest note, is the F major 11th chord – rooted in the fourth scale degree.

The F major 7 #11 can be broken into 4 triads;

The following diagrams show the shapes of the chords indicated in the notation above. Each three note sequence is a section of the overall extended 11th chord arpeggio;

Here's the interval structure of the four types of diatonic 7th chords in the major keys, based on the major and minor 3rds which occur between each chord degree;

|

| Dotted line separates symmetrical and asymmetrical chords based on their interval structure. |

The center interval in each of these 7th chords spans the 3rd Rail. Only the minor 7th chords have a major 7th in their centers. It takes a change in perspective to think of chords from the center outward, rather than from the bottom up, but it will give you a much more sophisticated understanding of harmony and a greater command of the fret board.

––––

The three minor 7th chords are rooted on the 2nd, 3rd and 6th scale degrees of a major key. The major 3rds at the center of these chords are rooted on the 4th, 5th and 1st scale degrees, respectively.

The I - IV - V center intervals on the 3rd Rail are essential landmarks on the fret board. We've already examined these positions in this post. The next diagram shows all the major 3rds spanning the 3rd Rail up to the 17th fret (If your guitar has 24 frets then you also get one there);

|

| Roman numerals indicate repective positions of major 3rds rooted on 3rd string. |

|

| Lower case Roman numerals indicate root positions of minor 7th chords rooted on 4th string. |

|

| Roman numerals indicate root positions of 11th chords on 4th string. |

In this position – starting from the center and moving outward – we first find the C major 3rd (C-E), the A minor 7th chord (A-C-E-G), then the F major 11th (more precisely F major 7 #11), consisting of six notes (F-A-C-E-G-B). So this form is, starting from its lowest note, is the F major 11th chord – rooted in the fourth scale degree.

The F major 7 #11 can be broken into 4 triads;

The following diagrams show the shapes of the chords indicated in the notation above. Each three note sequence is a section of the overall extended 11th chord arpeggio;

The F major and E minor are only playable as arpeggios because they have two notes on a string, while the three notes of the C major and A minor can be arpeggiated or strummed or plucked together.

All seven of these extended arpeggio forms can be treated the same way. Play the notes of each form in consecutive three-note sequences (triads) starting from the low note, then from the highest note of each form.

Of course, any of these forms can also be played in other note grouping combinations. For instance, in addition to the triads shown above, each extended arpeggio form can also be split into three 7th chords – not just the central 7th chord we began with. Below is notation showing the three 7th chords within the F major 7 #11 arpeggio;

Lets look at the interval structure of all of the diatonic 11th forms based on their scale degrees;

The dotted line in the diagram above separates the first two chords from the next four because the IV, II and VI chords all have internally symmetrical interval structures, while each of the others is individually asymmetrical, though they are all part of a larger symmetry. Also notice that the only two which share the same interval structure are rooted in scale degrees II and VI.

Next: 3rd Rail Chord Symmetries (Part 4), we'll examine the triads if the major 7th extended forms which become the II and VI rooted 11th chords.

All contents of this blog are © Mark Newstetter