Theoretically simple arpeggios are not so simple on the guitar. Playing the sequences of major and minor thirds which, at the simplest, can be expressed as "every other white key on the piano;"

Because arpeggios are actually chords, the notes in an arpeggio may be numbered accordingly. The first note of a simple arpeggio is the Root. The keyboard diagram shows an extended G dominant arpeggio in the key of C;

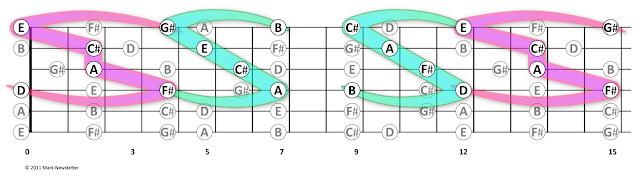

The equivalent arpeggio on the guitar is shown below;

If the convoluted blue pattern above is confusing, try breaking it in half. Here's the upper part;

... and the lower part;

As you can see, each half of the full extended arpeggio is quite symmetrical. When combined the form is more complex, but visualizing the dual symmetry makes it easier to navigate.

There are seven super-arpeggios in this system. Below you see them all, labeled for the major scale degree on which each one is rooted;

You can treat these arpeggios as we've done with the G dominant, playing the lower three strings and the upper four strings of each separately, then joining the upper and lower forms.

Here's notation for all nine patterns shown above;

Here are sound files of each 6-string arpeggio as shown in the diagrams and notation above;

You can find more about arpeggios elsewhere in this blog.

All contents of this blog are © Mark Newstetter

If the convoluted blue pattern above is confusing, try breaking it in half. Here's the upper part;

As you can see, each half of the full extended arpeggio is quite symmetrical. When combined the form is more complex, but visualizing the dual symmetry makes it easier to navigate.

There are seven super-arpeggios in this system. Below you see them all, labeled for the major scale degree on which each one is rooted;

Here's notation for all nine patterns shown above;

Here are sound files of each 6-string arpeggio as shown in the diagrams and notation above;

... E Mediant (Open position) Arpeggio

... G Dominant (3rd fret) Arpeggio

... B Leading Tone (7th Fret) Arpeggio

... D Supertonic (10th Fret) Arpeggio

... F Subdominant (1st Fret) Arpeggio

... A Submediant (5th Fret) Arpeggio

... C Tonic (8th Fret) Arpeggio

... E Mediant (12th Fret) Arpeggio

... G Dominant (3rd fret) Arpeggio

... B Leading Tone (7th Fret) Arpeggio

... D Supertonic (10th Fret) Arpeggio

... F Subdominant (1st Fret) Arpeggio

... A Submediant (5th Fret) Arpeggio

... C Tonic (8th Fret) Arpeggio

... E Mediant (12th Fret) Arpeggio

You can find more about arpeggios elsewhere in this blog.

All contents of this blog are © Mark Newstetter