One of the dangers of challenging the norm in any field is being misunderstood. The salvation from this fate, should it befall one, is the realization that the 'norm' is also misunderstood. Since no one really understands the norm, it's not abnormal to be misunderstood. That people don't understand something doesn't say too much about the truth or falsity of that thing.

Most beginners don't understand the way the fretboard really works. Not just from a mechanical, physical perspective, but a musical one as well. Presented with a diagram showing, say, the positions of the notes of the key of C on the fretboard, most would say that there doesn't appear to be a discernible logic to the positions of the notes.

What one comes to understand is that what is 'discernible' may not be obvious. You have to know how to look at things.

The trick is to have a

reason for choosing a particular way of looking at something. Music is not merely based on a set of arbitrary choices. The fixed tonal relationships of the diatonic system reflect natural harmonic principles. When you hear music, you are sensing vibrations (and you

are vibrating). These vibrations are recognized as 'music' because they follow identifiable patterns.

If you watch ocean waves rolling to the shore, you can see complexity in a single wave.

Each wave is really a combination of smaller waves. The white foam at the crest of a wave is where turbulence forms to scatter the light enough to turn transparent water opaque. Millions of tiny waves within the bigger wave. The waves come in rhythmic patterns. Some waves are smooth and don't break until they hit the sand. Some waves break before reaching the shore and are absorbed into bigger waves.

This is the ocean singing.

Music is streams of invisible waves, no less real than those in the ocean, which fill the air and set your tissues vibrating in sympathy. There is symmetry and structure inherent in the experience of music, so there is symmetry and structure in the musical tones as they are arrayed on the fretboard. That it appears at first to be a random array is a matter of perspective. There is, of course, randomness within order,

......

I began playing the guitar at age 9, had two formal lessons and decided to find my own way with the instrument. Consequently I took what I think of as 'The Long Slow Path.' What I had, and hope I still have, is diligence.

I also had somewhat formal music training in the New York public schools I attended, in which I learned to play the recorder and the viola. My mother, and some aunts, uncles and cousins played piano, so I learned a few things from them. I felt prepared to figure out the fretboard using the theory I'd learned in school, the left hand technique I was acquiring on viola in Junior High, and the chord structure I studied on the piano.

I could play scales, picked up chords quickly, and figured out how to sing and strum in two different rhythms at once.

But, like most guitar players, I avoided written music of any kind. But, I enjoyed training my ear to match the tones I'd hear on records with the guitar as I played. It was a great puzzle to try and solve.

That's where it gets confusing.

That the guitar fretboard is somewhat puzzling is common knowledge - especially among novice guitarists. The guitar student has to make sense of what seems to be an almost random invisible array of notes on the grid of the fretboard.

First of all; it's facing the wrong way! You have to be curious to play the guitar, because it plays hard to get. You can't get face to face with the guitar when you play. Because it's difficult to reconcile the 'upside-down' view one has of the fretboard when playing with the way it's represented on the page, reading for the guitar is a challenge for most students.

If you play for a while, you'll likely reach a point when you'll want to know something about the music theory you've avoided. Especially if you find yourself jamming with people who play other instruments.

Since players of other instruments aren't faced with the convoluted maze of fingering patterns that guitarists have to wrestle with, they have more time to come to terms with the link between notation and vibration. You'll probably be the worst reader in the room. You may end up having the piano player tell you the names of the notes your playing.

Avoidance is not a solution. Yet there are no shortage of workarounds available. Methods based on short cuts. Tablature is the most common short cut. No question that tablature is useful. It's a great form of short-hand. But it doesn't translate. Only a guitar player can make sense of tablature. Players of other instruments read the same basic standard music notation, not tablature. It's a given that if you take piano lessons, or violin lessons, or saxophone lessons, that you'll be taught to read notation.

Not so for the guitar. Students know that lots of famous guitar players get by just fine with little or no formal music theory. Guitar teachers, if they read music themselves, have to accommodate students who are hooked on tablature before they walk in the door.

Where tablature falls short is that it reveals essentially nothing about the relationships between the fret and string positions of notes and their musical identities, either in terms of tonality or rhythm.

Interval relationships are clear in notation. The timing and dynamics of notes is clear in notation. And notation is shared by many many instruments, bringing the guitarist 'into the fold.' Also, because notation is a true language, not merely typography, it can be verbalized and used to enhance communication between players. Tablature can't be read off the page verbally to coherently express the musical ideas it is supposed to represent. All you'd have is a series of string and fret numbers, which would be as meaningless to players of other instruments as the tablature itself.

Tablature does nothing you can't do with notation, though it does provide you with what amounts to a set of map coordinates which simplifies the process of knowing where to put your fingers and which string to pluck in what sequence. Sure it works as advertised, but that's not all there is to music, and the more you play, the more you begin to realize that.

Now, if tablature is an inadequate method of written guitar music, and you want to learn standard notation for the guitar while staying sane, what's the best way to go about it?

The classical method is basically to learn the notes in each fret position from the open strings to the 1st fret, to the 2nd fret, and on up, one by one. Become familiar with the open string position, then the next hand position, then the next. So that you become intimately familiar with the notes of the first three or four frets before moving up a fret.

... Though this works for millions of people, it's somewhat tedious to learn this way. And you never really get a clear picture of the overall note array on the fretboard.

This wouldn't matter if the fretboard was devoid of any recognizable symmetry in the way the notes are distributed. It's not. There is a recognizable, symmetrical pattern to the notes on the fretboard which can be used the way a piano player uses the pattern of black and white piano keys to navigate the keyboard.

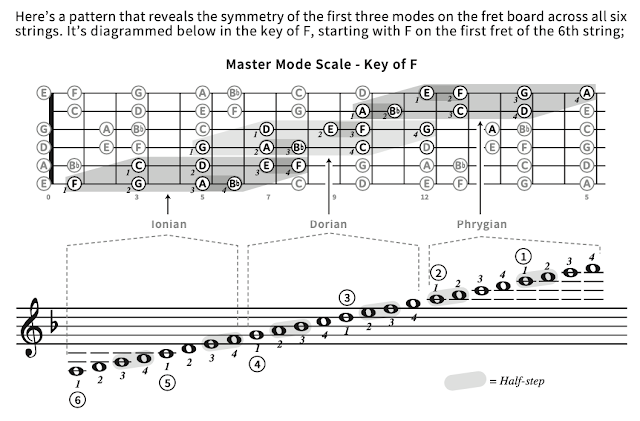

It's recognizable ... once you see it. The image below is an expression of the symmetry of the guitar fretboard I call

The Spiral Galaxy Pattern The essential elements are the clusters of half-steps, the natural tone axis positions and the central spiral pattern which connects the remaining note positions.

An animated version of the pattern can be seen here.

But unfortunately, it's invisible on the guitar. You have to imagine it as you play. When you do, finding your way around the fretboard becomes almost as easy as finding notes on the piano. And the logic of the pattern conforms nicely with standard music notation, which is the goal.

When you have a pattern in your mind, you can find your way around better. Using tablature is a little like having a map with nothing but a grid and no geographical features. You know the latitude and longitude of each location, but you can't see the roads or the land masses and the oceans.

Without a picture of the 'geography' of the fretboard, you are wandering aimlessly. With that picture, you are communicating with the guitar and it is communicating with you. The journey becomes the destination.

Fretography challenges the norm in saying that the fretboard begins in the middle, not at the open strings. There's a good reason for this. It's because, if you start in the middle it gets easier faster than if you start with the open strings.

The conventional bias toward learning the guitar from the open strings first, then moving up incrementally has understandable origins, and it's clearly the best way to learn un-fretted instruments like the cello and violin, since, without frets, the only 'fixed' tones are the open strings. When the open string is the only absolute reference point for pitch on each string, every note you finger on a fretless instrument has to be learned in reference to the open string. On the guitar this matters not at all.

Since the frets take care of the intonation of each note you play on the guitar, you don't have to worry that your finger is exactly, precisely, in the perfect spot, as long as it's next to the correct fret on the correct string. If you're playing a cello or violin, then finger position is absolutely critical.

So why start with the open strings? I believe that the standard method is an anachronism which is long overdue for an upgrade.