In the previous post, we examined the three minor 7th chords rooted on the 4th string and centered on the 3rd Rail, then added notes a third above and below the original four-note chord. The added high note is actually a 9th, and – since we are keeping the original chord root – the added low note can be thought of as a 6th (or a 13th).

Here's another example: If we take the tonic major 7th chord (C maj7) with the notes C-E-G-B as the Root-3rd-5th-7th respectively, the D added above the B of that chord is the 9th of the chord. The five notes comprise a C major 9th. The A added below the C is – theoretically – also a 6th above C. 6ths in chord structure are thought of as 13ths when added to 7th chords (or 9th chords), so the whole six-note sequence can be considered a C maj 9 add 13. And because the 13th (A) is now the lowest note in the chord, it may be called C maj 9 add 13/A. In chord naming, when a note other than the root is played as the lowest pitch, it is added to the chord name following a slash. The diagram below shows the relationships of these notes on the staff;

If we were to use the added low note as the root of these extended forms, we would call them 11th chords. For instance; A-C-E-G-B-D would be called an A minor 11th, F-A-C-E-D-G-B would be an F major 11th (actually, an F maj7 #11), etc. Of course, any three consecutive notes an a series of 3rds is a chord, so the sequence A-C-E-G-B-D contains four three-note chords; A min, C maj, E min, G maj. So you can choose to slice these patterns any way you want. However, the 7th chords comprising a single note on each of the four top strings are the most clearly symmetrical forms, and make a good core structure for purposes of study and practice, as well as providing clear landmarks for improvising and composing.

There are two major 7th chords in any major key. These are the 4th-string root position major 7ths in the key of C. They are F maj7 and C maj7, the I and IV chords of the key of C.;

Here are the extended patterns of the above chords;

This pair of extended major 7ths have the unique characteristic of being the only two identical extended chord forms, and are each internally symmetrical – comprising two minor-major-minor-major-minor-3rd sequences.

Here's the extended 6th scale degree minor 3rd (A minor) between the two major 7ths;

Returning to the key of C, here are the extended G dominant 7th (rooted on G at the 5th fret) and B minor 7 b5 (rooted on B at the 9th fret);

These chords are shown below as they are positioned on the piano keyboard;

Here's the notation for these two extended chords. Notice that their interval patterns (and their geometry) are the exact opposite of each other;

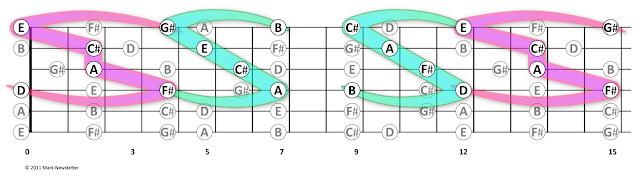

Now let's look at the major 7ths, the dominant 7ths and the minor 7 b5 chords all together on the fret board;

These chord forms overlap in interlocking patterns, all based on the symmetry which is centered on the 3rd Rail. Remember that – by most accounts – the odd tuning of the interval between the 2nd and 3rd strings is a flaw – a glitch. But by treating that 'odd' interval as the fulcrum of the fret board, we see that there are very useful symmetries which stem from it.

In PART 3 we'll continue to explore the possibilities of these arpeggio forms.

All contents of this blog are © Mark Newstetter

Here's another example: If we take the tonic major 7th chord (C maj7) with the notes C-E-G-B as the Root-3rd-5th-7th respectively, the D added above the B of that chord is the 9th of the chord. The five notes comprise a C major 9th. The A added below the C is – theoretically – also a 6th above C. 6ths in chord structure are thought of as 13ths when added to 7th chords (or 9th chords), so the whole six-note sequence can be considered a C maj 9 add 13. And because the 13th (A) is now the lowest note in the chord, it may be called C maj 9 add 13/A. In chord naming, when a note other than the root is played as the lowest pitch, it is added to the chord name following a slash. The diagram below shows the relationships of these notes on the staff;

If we were to use the added low note as the root of these extended forms, we would call them 11th chords. For instance; A-C-E-G-B-D would be called an A minor 11th, F-A-C-E-D-G-B would be an F major 11th (actually, an F maj7 #11), etc. Of course, any three consecutive notes an a series of 3rds is a chord, so the sequence A-C-E-G-B-D contains four three-note chords; A min, C maj, E min, G maj. So you can choose to slice these patterns any way you want. However, the 7th chords comprising a single note on each of the four top strings are the most clearly symmetrical forms, and make a good core structure for purposes of study and practice, as well as providing clear landmarks for improvising and composing.

There are two major 7th chords in any major key. These are the 4th-string root position major 7ths in the key of C. They are F maj7 and C maj7, the I and IV chords of the key of C.;

|

| The notes are shown in descending order on the staff because it visually follows their layout in the fretboard diagram. Play the notes in ascending and descending sequences. |

This pair of extended major 7ths have the unique characteristic of being the only two identical extended chord forms, and are each internally symmetrical – comprising two minor-major-minor-major-minor-3rd sequences.

Here's the extended 6th scale degree minor 3rd (A minor) between the two major 7ths;

|

| F major 7th - A minor 7th and C major 7th extended arpeggio forms. |

Here's the same configuration in the key of D;

| |

|

... and in the key of A;

|

| F# minor is shown in the lowest and highest positions, around the A maj. 7th and D maj. 7th. |

|

| The extended dominant 7th becomes an E minor 11 b9 when the lowest note is taken as the root. The extended B minor 7 b5 becomes a G dominant 11th when its lowest note is taken as the root. |

Here's the notation for these two extended chords. Notice that their interval patterns (and their geometry) are the exact opposite of each other;

Now let's look at the major 7ths, the dominant 7ths and the minor 7 b5 chords all together on the fret board;

These chord forms overlap in interlocking patterns, all based on the symmetry which is centered on the 3rd Rail. Remember that – by most accounts – the odd tuning of the interval between the 2nd and 3rd strings is a flaw – a glitch. But by treating that 'odd' interval as the fulcrum of the fret board, we see that there are very useful symmetries which stem from it.

In PART 3 we'll continue to explore the possibilities of these arpeggio forms.

All contents of this blog are © Mark Newstetter

No comments:

Post a Comment